But can you destroy the power base for fossil fuels without creating massive injustice?

Margaret Thatcher is often taken as an early pioneer in climate change among leading politicians. Her speech to the Royal Society in September 1988 helped propel climate change onto the political agenda not just in Britain but around the world.

But her government was much more important in shaping the course of Britain’s actions on climate change a good deal earlier in her period of office.

Her decisive intervention was rather in the assault on the National Union of Mineworkers (NUM), with the strike of 1984-5 as the decisive event.

Freedom

Many are deeply reluctant to acknowledge this, for various reasons. Recognising the role of the outcome of the miners’ strike in making UK climate leadership possible is discomforting to say the least. For those in the labour movement, it reopens old wounds.

For those pushing for stronger climate action, it makes the tension between the need to overcome opposition by major fossil fuel corporations, and the desire for a “just transition”, abundantly clear.

Can we undermine corporate power without leaving the workers they employ and the communities that depend on them stranded?

What the miners’ strike story tells us is that one of the only actual transitions away from fossil fuels we have seen globally has been a profoundly unjust one, enabled by the destruction of working class communities.

Thatcher’s new brand of conservatism saw trade unions as fundamental obstacles to creating 'free' societies, and consequently some of her government’s earliest actions were to restrict unions’ freedom to organise.

Mechanisation

Thatcherites sought to impede the capacity of trade unions to disrupt society in order to make gains for workers, and in the process fundamentally reimpose more authoritarian rule by and for business.

But for deep historical reasons, no union was more important than the NUM. The NUM was the most important union to crush, because of its unparalleled capacity to disrupt the economy through its control of the supply of coal. Miners, have, as Timothy Mitchell has shown, had unique capacities to disrupt industrial societies.

The ability of those workers to disrupt the flow of coal was crucial not only to economic gains for workers and redistribution of wealth, but also indeed integral to the creation of mass democracies in Europe and North America. Coal miners and allied workers had gone on strike in the early 20th century specifically to get universal (male) suffrage.

Thatcher, following writers like Hayek and Friedman, was explicitly opposed to that sort of democracy, and sought to recreate institutions that limited the power of workers to shape political decision making.

But can you destroy the power base for fossil fuels without creating massive injustice?

Mining as a source of employment in the UK had already declined steadily in the first half of the 20th century from its high point of 1.038 million miners in 1914, and then more quickly from the 607000 miners in 1960 onwards, in part because of mechanisation, in part due to opening up to international competition.

Vocal

Despite this decline, the NUM remained one of the most powerful unions in the UK, with capacity to engage in significant disruptive action.

Edward Heath’s government had been crippled by a wave of strikes during the early 1970s, and most important of these were those organized by coal miners and power workers.

These had brought Britain to a standstill with three-day weeks and rolling power cuts, forcing Heath to hold an election in 1974, that he lost, campaigning on the slogan “who governs Britain”.

Thatcher was determined not to see that repeated: attacking the NUM became very rapidly a key part of Thatcher’s strategy when she came into office.

Through the first few years of her administration her government prepared itself for a new confrontation with the NUM. Then energy minister Nigel Lawson (and, with delicious irony, Britain’s future climate denier-in-chief) was particularly vocal in arguing for the “overriding need to prepare for and win a strike“.

Brutal

The need for preparation was underscored after the NUM went on strike in 1981 over a proposal to close 23 pits, and the government was forced to backtrack.

Preparation for a future major strike included stockpiling coal, coordinating police forces to combat picketing aggressively, and waiting until after the 1983 election when they would be ready.

The immediate trigger for the strike was, as in 1981, proposals for pit closures and job losses. Thatcher transformed the existing trend towards declining numbers of pits and miners into open class warfare.

The effects of the announcement were clearly predictable. The NUM leadership of Arthur Scargill and Mick McGahey had arguably no choice but to take the bait and in 1984 a large indefinite strike started within the coal mining sector.

This is not the place to detail its twists and turns, but it is worth noting given its implications for climate politics, that the strike was brutal. Six people were killed.

Breakdown

Many others were injured in long-running confrontations between police and picketing miners. Mining communities were acutely affected by the strike itself.

Solidarity with miners among trade unions was generally strong, but nevertheless the loss of income in communities which were often single-employer towns meant the whole town or village was drastically affected.

The outcome of the strike was the best that Thatcher could have hoped for. The NUM left the strike defeated and with a steady drip of miners heading back to work as the costs of being on strike to them and their families became too great.

The mines that were to be shut were all closed, and the strike result set British society on a dramatically different course, emboldening Thatcher to engage in her desired programme of curtailing union rights and privatisation.

For thinking about climate breakdown, what matters is the trajectory of Britain’s relationship to coal that the strike created. This is where Thatcher’s impact on Britain’s response to climate breakdown is much more significant than her 1988 speech.

Reversing

In the short term, Britain still consumed more or less the same amount of coal as prior to the strike. But employment in coal mining declined dramatically: in 1980, there were around 237000 workers in the coal industry, by 1990 there were around 49000.

The number of UK mines declined in the same period from 213 to 65, and coal output fell from 130m tonnes to 93m. The UK was still burning coal, but the UK coal industry was in rapid decline.

When climate change hit the agenda in 1988, the decline of coal was not immediately obvious. Energy analysts still routinely referred to it as “King Coal”: the linchpin of the energy system.

Some, like Chatham House’s Michael Grubb still perceived the effects of the 1984-5 strike as potentially reversible. There would be a general election in 1991 or 1992, and it looked highly plausible that Labour would win.

Neil Kinnock would become prime minister, and while he was hated by the NUM leadership, he was from a South Wales coal mining background. The Labour manifesto committed a future Labour government to reversing the rise in coal imports to support UK coal mining.

Power

It is much clearer in hindsight, however, that the strike undermined the power base supporting coal in Britain, with profound effects on the trajectory of UK climate policy.

Thatcher had indeed destroyed the most powerful union. But she had also destroyed a large state-owned corporate entity – the National Coal Board - with vested interests in keeping coal being produced and used within the UK.

Coal had been taken into public ownership in the wave of nationalisations in the 1940s after the Second World War and was still a nationalised industry when Thatcher came to power. It was renamed British Coal and privatized in 1987, after which its decline was precipitous, closing its last mine in 2015.

The emergence of North Sea oil and gas was also crucial to the Thatcher government’s assault on coal. Britain became an oil and gas producer during the 1980s.

With the new availability of domestic natural gas, and a continued desire to undermine any remaining power that the NUM might have, the government structured the regulation of the newly privatised electricity industry to favour natural gas over coal.

Destruction

Gas had other benefits over coal, notably regarding air quality and acid rain but their political advantages in terms of continuing the assault on coal were the most important benefit for the government.

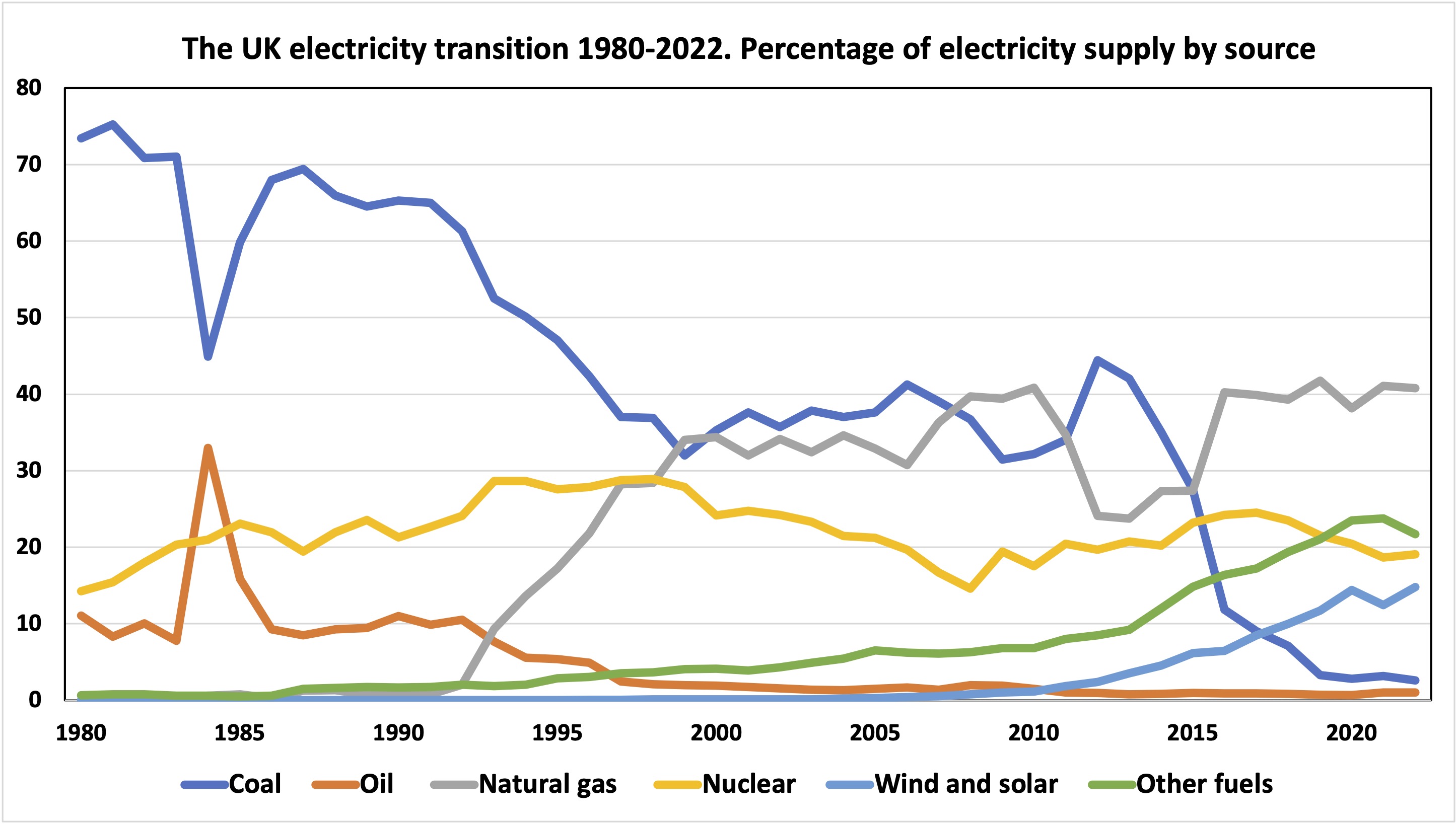

The result of this regulation of the newly privatised electricity industry was “the dash for gas”. During the mid-1990s, the British electricity system saw a noticeable decline in coal use and a noticeable increase in natural gas (see figure).

By 1997, when Britain signed the Kyoto Protocol, coal had already declined to below 40 percent of electricity supply, and the share taken by natural gas had risen from zero to about 45 percent.

Environment secretary John Gummer (now Lord Deben, until recently chair of the UK climate change committee) was able to start boasting about Britain’s achievements in cutting its emissions because of the dash for gas.

Natural gas emits 40-50 percent less CO2 per unit of energy than coal. This switching from coal to gas progressively reinforced the destruction of any ability that forces promoting coal might have to resist the trend.

Source: UK Government.

Emissions

Fast forward to 2007, when the New Labour government of Tony Blair was developing and enacting the Climate Change Act. By this time, coal mining in the UK had all but disappeared (there were 13 mines left, and only 6000 miners), and there were no powerful forces left defending it.

The logic of rolling five-year carbon budgets – central to the design of the Climate Change Act – created a focus on short-term cuts which favoured continuing the path the UK was already on in climate policy, centred on reducing coal’s share in electricity production.

In 2013, responding to concerns that the EU’s Emissions Trading Scheme was not delivering the cuts it needed because its carbon price was too low, the government instituted a “carbon floor price”, which penalised coal as the highest carbon fuel, even further. As coal use started to plummet, the government then introduced a simpler signal, by announcing in 2015 that coal use would simply be phased out entirely by 2025.

The UK’s phase out plans for coal were widely lauded and have been integral to the UK’s ability to claim global leadership on climate breakdown.

At the time of writing Britain’s emissions are down 49 percent on their 1990 levels, according to UNFCCC figures. Hardly any other country can claim this level of emissions cuts.

Compensate

Some of this decline is due a process of deindustrialisation in the UK. But the lion’s share has come from coal shifting from 70-80 percent of the UK’s electricity supply, down to basically zero.

The figure above shows this dramatically in the share of electricity generation. In crude terms, this shows a transition from coal to gas from 1991-98, then followed by a transition from coal to wind, solar, and biomass (the bulk of the “other” category), from 2012 to the present day.

Looking beyond the UK is instructive. In other “leading” countries where coal interests remain integral to their economy, their emissions have not declined as much as Britain’s have.

Germany is the most instructive example, where despite extensive climate action in various areas, coal remains a significant contributor to electricity production at 31 percent in 2022.

Germany’s emissions have declined by 41 percent between 1990 and 2020, so still relatively good (Canada’s for example are up 13 percent in that time period, and the US’s are only down 7 percent), but this has entailed a great deal more policy activism in various other areas – transport, housing, and so on – to compensate for the inability to reduce coal in the electricity mix.

Closed

They also have significant corporate and union power supporting the continued mining and burning of coal. Scholars of energy transitions call this “incumbent power“, and this is central to explaining the difference between the UK and Germany.

In the UK incumbent power of coal interests has been eliminated while in Germany and elsewhere it remains strong. Conversely of course, this means that UK climate policy is now at a crunch point: the “easy win” of eliminating coal has run its course and policy now needs to focus on other areas which are more difficult because incumbent power is still considerable.

No-one really wants to acknowledge the role of the miners’ strike in making British climate leadership possible. When it is occasionally mentioned, people get shouted down.

Admittedly, the most prominent such mention was shouted down because it was Prime Minister Boris Johnson doing so with his characteristic poor judgment and taste.

“Thanks to Margaret Thatcher, who closed so many coal mines across the country, we had a big early start and we're now moving rapidly away from coal altogether”, he said in August 2021, reportedly laughing while saying it.

Assault

Beyond Johnson adding insult to injury, the legacy of the miner’s strike is never mentioned in public life. It is like a dirty secret.

Some Conservatives who harbour guilt over the destruction of a “noble” industry (Norman Tebbit for example) do not want to acknowledge the link, but more commonly they simply see coal mining and climate breakdown as two separate domains, despite the obvious connections.

For Labour it is a distinct sore point, since the strike itself was the source of much division within the Labour Party and broader movement, ending up with a leadership by 1997 that was distinctly hostile to the NUM and many other unions.

Nevertheless, Blair was always constrained by the links between party and unions from acknowledging explicitly the role of the assault on coal enabling them to claim UK climate leadership.

Incumbents

But it is also the case that those, mostly on the green left, arguing for more aggressive climate action, and particularly for “just transitions”, are just as reluctant to think about the miners’ strike and its implications. It is distinctly uncomfortable to acknowledge for those involved in unions or the labour movement that the destruction of union power may have aided climate action, and those involved in both have powerful reasons to keep the two separate.

When the legacy of the strike has come up, one line of argument is that “Thatcher wasn’t motivated by climate concerns”.

Nicola Sturgeon, criticising Johnson’s quip, stated that the devastation caused by Thatcher’s assault on the miners “had zero to do with any concern she had for the planet”. This is obviously true, but only relevant if we think that motivations matter to climate breakdown more than the trajectory of emissions.

If, rather, the central lesson of the miners’ strike is that not only did it destroy the NUM, but it also destroyed the coal industry as a whole, and that it was the destruction of the power base for supporting coal that has enabled the UK to cut its emissions so far, then it draws our attention to this key political question of destroying the power of 'incumbents' as the necessary condition for responding adequately to the climate crisis. Power relations matter more than motivations.

Unjust

But can you destroy the power base for fossil fuels without creating massive injustice?

Britain’s ability to achieve significant emissions cuts has come on the back of the destroyed mining communities across northern and central England, South Wales and parts of Scotland.

Many of us thinking about climate breakdown want to talk about 'just transitions', but the coal transition in Britain has been anything but just.

There are fewer jobs in oil and gas than there were in coal, so it might be possible to design strategies to retrain those workers, as for example the Alberta NDP government did in its short time in office.

But in a zero-carbon world, that also has to be extended to farming, steel, cement, automobiles, and many more sectors. The legacy of the miners’ strike remains a troubling case of a successful, but highly unjust transition.

This author

Matthew Paterson is professor of international politics at the University of Manchester. His latest book is In Search of Climate Politics (2021).