It is in our hands to see that the hope of the future is not lost because we were too sure that we knew the answers, too sure that there was no hope.

“As impressionable young people, when we were 12 or 13 years old, we were convinced we were going to die in a nuclear holocaust,” the director Christopher Nolan said on the release of ‘Oppenheimer’, his latest blockbuster. “I think very much the way kids these days feel about climate change.”

My father’s approach to parenting was to tell me everything. I remember being really young when he told me that some physicist called Oppenheimer had done some calculations on a scrap of paper before he tested the first atomic bomb. The theoretical proof confirmed the nuclear test would not set off a chain reaction that would ignite the Earth’s entire atmosphere.

That first test, Trinity, did not in fact kill everybody and everything. But the actual calculations, my dad claimed, proved to be wrong. I took a very keen interest in Raymond Briggs’ When the Wind Blows, and the BBC programme Threads, after that. The adults, I learned at that early age, were not to be fully trusted with my safety.

READ: TENET AND THE DIALECTIC OF CLIMATE ARMAGEDDON

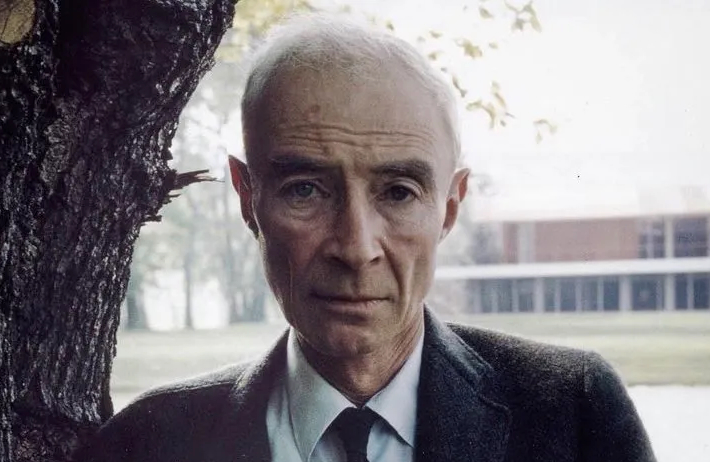

The biography of J Robert Oppenheimer is among the most interesting of our historical era. The “father of the atomic bomb” led one of the most significant lives in the applied sciences in human history. Oppenheimer was director of the Manhattan Project at Los Alamos from March 1943 to October 1945, leading a team of 6,000 scientists and military experts. He didn’t press the button. But he built it. When it was pressed he reflected on a phrase from the Sanskrit Bhagavad-Gita. “Now I am become Death, the destroyer of worlds.”

Destroyer

Oppenheimer was also a communist, or at least had a keen interest in communism. The film reports that he read all three volumes of Karl Marx’s Das Kapital in the original German. He was madly in love with Jean Tatlock, who in turn was a member of the Communist Party. She also suffered what we today might recognise as internalised homophobia of the most detrimental kind. His wife, his brother, and many of his friends had at one time or other been card carrying members of the party.

This is a story about the relation between nuclear power and political power. The Trinity Test at Los Alamos is a switch that can never be switched off again. The film was launched with a live countdown to 16 July 2023 - marking 78 years since the first detonation of an atomic weapon.

The success of those early atomic tests has defined the contours of our civilization ever since. The US murdered as many as 200,000 people when it bombed Japan, and did so after the Second World War was certainly at its end.

It is in our hands to see that the hope of the future is not lost because we were too sure that we knew the answers, too sure that there was no hope.

Russian spies stole the research of the Manhattan Project and Stalin built the largest nuclear arsenal in the world. The weapons fueled nuclear energy, including the uranium that today burns at Chernobyl and Zaporizhzhia - with the latter apparently currently primed with explosives by the Russian occupiers of Ukraine.

Thriller

This, a most consequential moment in our collective history, has been dramatised by Christopher Nolan, the most ambitious and audacious director of his generation. Oppenheimer himself has been brought back to life by Cillian Murphy, the most charismatic and talented actor currently working.

The resulting film, Oppenheimer, is cataclysmic.

In the immediate aftermath of the film I feel like my intellect has been subsumed into some kind of detonating device and used to blow my emotional being into a thousand radioactive pieces. I just don’t have the words or the imagination to describe the love, the fear, the fury that results. Nolan had claimed that he never wanted to “make a didactic film - ever.” But with this, his 12th feature film, he has utterly failed in that regard.

This is among the most powerful and important moral fables of our times. Emily Blunt, who plays Kitty Oppenheimer, remarked that Nolan had "Trojan-Horsed a biopic into a thriller". This film, with a $400 million budget, could implant an important anti-nuclear ethic into a new generation of Americans. As we as a species have to abandon fossil fuels and find other ways to power our lives, this message could not be any more vital.

I guess a good place to start in describing this film is the profound and pure admiration that Nolan manifests for Oppenheimer as a human being, and as an American. The screen is literally filled with the testimonies provided by the scientists who worked with him, the women who loved him, and the activists who heard him speak. They speak to his intellectual integrity and honesty.

Indeed, his nemesis Lewis Strauss is presented in black and white - an unimaginative, two dimensional, self seeking political charlatan. Likewise, the American military - even where we are presented with evidence that some of its members, its generals, have integrity - is exposed as hubristic, ignorant, hypermasculine and genocidal.

The dilemma, the moving force of the film, is how Oppenheimer - this man of reason and integrity - could build an atom bomb that he knew would kill tens of thousands, and kill indiscriminately. The use of a nuclear weapon is literally a war crime.

Ignition

Nolan gives his subject everything he has got. He deploys his best actors, his best filmmakers, and best instincts. The epic scale of the production of the film corresponds with and reinforces its theme. Nolan is a director who must push his work and his art to its logical extreme. This is the first time IMAX black and white film has ever been used in human history. This echoes the fact Oppenheimer was motivated by an overwhelming desire to pursue his science, and to complete the task which has been assigned by history to him.

Nolan has worked with Murphy on six prior collaborations. But these are mere dress rehearsals. Murphy delivers a pitch perfect performance during his first lead role for the director. I anticipated writing, for this review, very clever things about Murphy’s previous roles as Jim in 28 Days Later and the physicist Robert Capa in Sunshine - both of which explore the eclipse of humanity - adding depth to his outing as Oppenheimer.

But, in fact, there is no Murphy on the screen. It is pure Oppenheimer. Every atom of that actual historical figure - every blemish, every feeling, every equivocation, every ethic, every sole destroying regret - is brilliantly reconstructed.

Ludwig Göransson composed the score for the film after delivering a groundbreaking soundscape for Tenet, Nolan’s previous venture. Here Göransson paints with colours which are as vivid as the IMAX frames and the storytelling. There are moments of almost silence, matching Oppenheimer’s own soft voice, contrasted with explosions of sound of atomic scale. It always sounds like you are right there: in the hearing, at the test site.

The film explores the fact that the fear that the Nazis would win the nuclear arms race was very real, especially for Jewish Europeans including Oppenheimer and Albert Einstein. We get to witness this history from the front row. And we see how even after Hitler was dead in a bunker, the American military remained just as determined to develop and deploy a weapon that could end all of human life.

The fear that a nuclear bomb could end up in the wrong hands is slowly superseded by the dreadful realisation that the bomb came into existence, was built, by the wrong hands. The American state, as imperialist and as murderous as any, ensured that the weapon was tightly gripped in its fist.

We witness, further, how the scientists once they have delivered the nuclear bomb are slowly and deliberately prised away from any decision-making process relating to when such a bomb would and should be used. Oppenheimer was discredited not because he was a communist, but because he was a scientist, the father of the nuclear age, who tried to warn of the dangers of that science.

Catastrophe

The people who were the first and the closest witnesses to the first atomic ignition in human history, who were best placed to extrapolate how this newly unleashed power might take us, were deliberately blacklisted and shamed so that the military could move forward with its mass production of warheads, and to use them to commit and threaten mass murder.

The film follows how Oppenheimer’s proximity to communism may have led to him being selected to develop a nuclear weapon, and was unceremoniously used to destroy him once he had achieved that end. The story we are told in this film is more faithful to the facts than most contemporary histories of those events.

Oppenheimer developed an interest in workers’ rights and communism during the great depression in the US. He donated to socialists fighting the fascists in the Spanish Civil War, regularly attended events and read the People’s World newspaper.

His wife Katherine Puening, known as Kitty, brother Frank Oppenheimer and his one time girlfriend Jean Tatlock were all for at least a time members of the Communist Party. These connections were well known to the US military when Oppenheimer was recruited to head the Manhattan Project. The film suggests this community of communists left the party, or created some distance, when it stopped being an agent for the working class and instead became a tool used by Stalin to deliver his foreign policy objectives.

Woe

Oppenheimer was a thoroughgoing intellectual, beyond his specialism in physics. He had a profound understanding of the consequences of his actions. He also suffered from acute depression, and “owned” the horror that his invention had and could unleash. He believed the use of the nuclear bomb was mass murder. He confessed to Harry Truman, “Mr. President, I feel I have blood on my hands.” He was not alone.

The bomb was only deployed after the Nazis had been defeated. Albert Einstein, whose letter to President Franklin Roosevelt had initiated the Manhattan Project, said: “Had I known that the Germans would not succeed in producing an atomic bomb I never would have lifted a finger.” When Einstein heard about Hiroshima, he lamented "woe is me".

Nor could the scientists take credit for the defeat of Japan. Admiral Nimitz, the commander in chief of the US Pacific fleet, has said publicly: “The Japanese had, in fact, already sued for peace. The atomic bomb played no decisive part, from a purely military point of view, in the defeat of Japan.” The effects were horrifying, even beyond the death toll. John Hersey reported in 1946 the reality of melted eyeballs and people vaporised leaving only shadows etched onto walls.

Suicide

Oppenheimer, following the deployment of his nuclear bomb, called for international limitations on the weapons, and also of nuclear energy. He warned that the arms race would result in the development of killing machines that could destroy the whole of civilization, the whole of humanity.

Cynthia Kelly, the founder and president of the US Atomic Heritage Foundation, has said: “He was opposed to pursuing the hydrogen bomb, the ‘superbomb,’ because that was 1,000 times more powerful than Hiroshima and Nagasaki.”

But as he raised these warnings he was smeared with his long known communist connections. A security hearing to investigate his loyalty to the United States was held at the height of McCarthyism. He was blacklisted in 1954 and the US stripped of his security clearance.

The FBI tapped his phones unlawfully. Tatlock, the communist psychiatrist who he still deeply loved, committed suicide during this period. Some in her family suspect American intelligence, which was bugging and following her, played a more significant role in her death than has been officially recognised.

Catharsis

As a communist, or at least 'fellow traveller', Oppenheimer tried to maintain a firm grasp on his belief in the good of humanity, an optimism for our collective future. In particular, he retained a faith in science, and reason. He wrote: “[F]or the nature which we must enlist is that of man; and if there is hope in it, that lies not least in man’s reason."

He continued: “The past is in one respect a misleading guide to the future: it is far less perplexing… It is in our hands to see that the hope of the future is not lost because we were too sure that we knew the answers, too sure that there was no hope.”

This optimism does not bleach out the impact of Nolan's biopic. The director admits: “[T]here’s an inescapable nihilism that creeps in with the underlying reality that he changed the world in a way that can never be changed back. There’s no real catharsis there.”

Revivify

Nolan was impacted by the discussion of nuclear war during his own childhood. He was cognizant of the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament and Greenham Common. "While our relationship with that fear has ebbed and flowed with time, the threat itself never actually went away," he observes.

I don't know if my father's story about Oppenheimer is exactly right. What is clear is that Nolan created this film as part of an ongoing conversation with his own children about the awful potential of nuclear weapons.

Indeed, Flora, his oldest daughter, appears in the film as one of the victims of the nuclear explosions that troubles Oppenheimer's waking dreams. Nolan observed: "The point is that if you create the ultimate destructive power, it will also destroy those who are near and dear to you."

Oppenheimer and his fellow scientists really did think a chain reaction, a nuclear fire that would consume the whole Earth, was possible, if extremely unlikely. Arthur Compton agreed to the test after calculating a less than one in three million chance of total annihilation. “It would be the ultimate catastrophe," he conceded. "Better to accept the slavery of the Nazis than to run the chance of drawing the final curtain on mankind.”

We now know, through their experimentation, that this was not the case. However, the threat posed by the existence of nuclear weapons and nuclear energy remains very real.

A total of $82.9 billion was spent by the nine countries armed with nuclear weapons on those deadly arsenals in 2022 alone. The US alone spent $43.7 billion. The tragedy at Chernobyl and the current madness unfolding at Zaporizhzhya, both in the former Soviet Union, revivify the possibility that a nuclear accident could end human life.

Armageddon

When the three hour film came to a close, I found myself in the third row simply sobbing. But the feeling I had was not one of awe or hopelessness. Instead, I felt renewed in the belief that there is serious work to be done - a project more ambitious and historic than the one achieved at Los Alamos.

The world has this year woken up to the reality of climate breakdown. This is the hottest our climate has been for a million years, according to the scientist James Hansen. There are record breaking temperatures in China, the United States and across northern Africa and southern Europe. The sea ice extent in Antartica has never been so low at this time of year. The ice caps are melting in front of our eyes.

There are approximately 200 nuclear power stations at sea level on this planet. If the sea rise continues the cooling systems of every single one of those could be seriously jeopardised. This threat will arrive at the same time, all at once.

Oppenheimer’s terrible invention still has the power to be the destroyer of worlds. We cannot unring the bell. We are going to have to transform every aspect of our societies to stop the burning of fossil fuels, and the use of nuclear power, if we collectively are going to survive this century. His faith in reason, his determination, his ethics are needed again to make sure that the potential for nuclear and climate armageddon is not realised.

This Author

Brendan Montague is the editor of The Ecologist online.