The thickets are a gathering place for marginalised human communities and practices as much as they are for endangered nonhuman species.

Endless high-rise buildings, modernist spaceship-like constructions, and gargantuan Soviet-era monuments of communists and workers. Before I arrived to Kyiv as a naïve PhD student, I pictured grey concrete and lots of it.

This article is published in partnership with Ukraine Lab.

And while my impressions formed from afar were not entirely false, they were lacking to say the least. It irks me that this greyness is the first, and often only, thing people think of when they imagine Kyiv – a city whose symbol is a horse chestnut leaf, begging us to find the green among the grey.

**

June 2021. A year ago. A different world. We’re gliding down the Dnipro on a riverboat at a fashion show by Mikhail Koptev, Ukraine’s premier ‘trash’ designer, who left Luhansk for Kyiv after Russia invaded Ukraine in 2014.

Portside, we look up a hill past an all-but-fully-nude catwalker into the greenery of Hryshko National Botanical Garden. Glancing starboard past a leaf sellotaped to the groin of another stumbling model, we see Hidropark, one of several forested islands on the Dnipro, which splits Kyiv’s right and left banks.

My friends Grant and Hugo who visit regularly from Berlin are surprised by Kyiv’s green lushness – an aspect of the city which seems to get lost in translation. Kyiv has been known as a “green city” in the reference books since Soviet times. But for many foreigners, this comes as news.

One afternoon, my friend Dmytro Chepurnyi and I were out for a wander. Dmytro, a researcher and curator from Luhansk whose family home has been occupied since 2014, has lived in Kyiv for 11 years and is well acquainted with the city’s nooks and crannies.

“So, what are they, these Kyiv thickets?” I asked, having never heard this term before. “They’re these green zones around the city,” he replied, “and they’re filled with political potential.”

The Kyiv thickets are, as the name suggests, dense patches of thick greenery that occupy the margins of the city, akin to the ‘brachen’ of Berlin.

Often liminal spaces suspended between rural and urban, nature and society, they are a gathering place for marginalised human communities and practices as much as they are for endangered nonhuman species.

Weekend dérives with Dmytro and his crew of artists, photographers, and researchers allowed me to become intimately acquainted with several of the Kyiv thickets, spending time with the more-than-human communities that call them home.

ECOLOGICAL THICKETS

The thickets are a gathering place for marginalised human communities and practices as much as they are for endangered nonhuman species.

Unable to shake my caffeine buzz after completing a thesis chapter in the early hours of the morning, I once walked from Podil – Kyiv’s old centre, where I lived – to Vyrlytsia Lake.

I left my apartment at around 5am as the morning sun was still burning through the dewy atmosphere. I headed straight for the river, where the buzz of mosquitoes was audible in the morning solace.

Crossing the Dnipro over Paton Bridge, I touched down on the left bank and walked randomly in a daze for a couple more hours, plodding through residential districts.

Despite looking uniform and repetitive, they remain endlessly fascinating due to the unusual architectural modifications residents are constantly making to them.

Eventually, I came to the end of the concrete jungle, crossed a motorway, and found myself looking at a huge expanse of water. My unintended destination had arrived. Later, I’d find out its name.

“Kyiv is a concrete block,” says Anastasiia Hmyrianska, an activist from Kyiv who leads the campaign to protect Vyrlytsia Lake from development. “This makes it difficult for birds to fly over without getting exhausted.”

The Dnipro River is an ecological corridor of global importance, facilitating the migration of a host of species from Scandinavia and northern Russia to the south.

The lake I’d spontaneously stumbled upon while drifting through the city that morning turned out to be one of the few migration stopovers left where these amazing avian travelers can rest their weary wings.

Hmyrianska tells me that it’s also a crucial nesting place and a stop-over for rare migratory birds.

Every year, Kyiv’s largest colony of black-headed gulls makes its home here, among over 60 other bird species that are protected by the Bonn and Bern Conventions.

Between 2016 and 2021, ornithologist Natalya Atamas recorded the presence of the red-necked grebe, little tern, peregrine falcon, and black-tailed godwit in addition to many others.

**

The diversity of habitats in Kyiv, especially on the banks of the Dnipro, is quite astonishing. Osokorky, for example, hosts six different habitat types including reservoirs, floodplains, swamps, shrub, and forest, and is home to 170 bird species as well as several species in the red book of Ukraine, like the emperor dragonfly and the northern crested newt.

Other areas, like Zhukiv island and Koncha-Zaspa provide a glimpse back in time according to ecologist Oleksiy Vasyliuk, “showing what the banks of the Dnipro looked like before anthropogenic disturbance.”

But not all the Kyiv thickets resemble “pristine” or “untouched” natural habitats, not that the terms “pristine” or “untouched” are useful for environmentalism in the contemporary era.

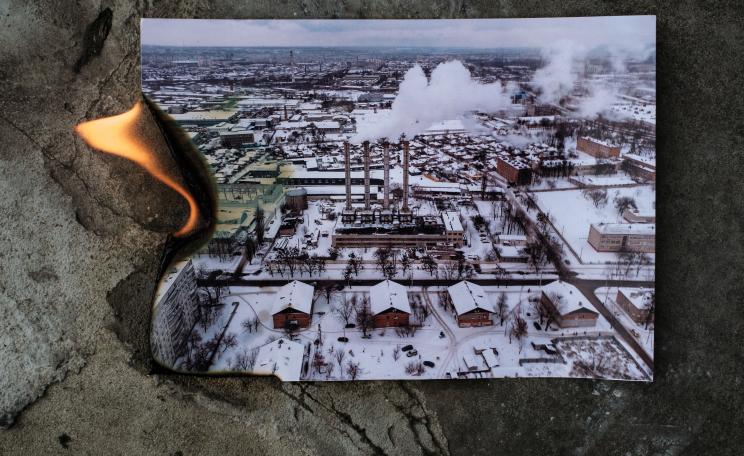

Following the deindustrialisation of the 1990s, nature began to spontaneously emerge amidst emptying green and brownfield sites. Since the economic rebound of the 2000s, however, the thickets have come under threat from commercial and residential development – spheres which remain steeped in corruption throughout Ukraine.

Like other marginal, seemingly abandoned, or unused urban spaces, developers often view the Kyiv thickets as wastelands. But there is nothing wasteful about these spaces. Indeed, ‘wasteland’ serves only as a convenient descriptor for jackpot-eyed developers who see the thickets as wasted opportunities to be cashed in on.

PROTECTING THE THICKETS

Kyiv’s green spaces are the subject of a host of national and municipal laws, but the legislation protecting them is limited and rarely enforced, while there is “an absence of liability for breaching the rules.”

Many of the Kyiv thickets are simply not on the map, making them ‘vulnerable’ in the words of Nastya Kuzmenko and Yaroslava Kovalchuk, the editors of Green Kyiv, a critical travel guide to Kyiv’s urban natures.

Yet despite this floundering legal system and entrenched corruption, attempts to develop Kyiv’s thickets and green zones are met with strong opposition by a lively community of Kyivan activists.

‘Save Horbachykha’, for example, is an organised collective that protects Horbachykha, a thicket on the left bank of the Dnipro, which is part of the Dnipro ecological corridor and home to myriad endangered and protected species of flora and fauna, including the Eurasian beaver and Eurasian otter.

Cultural and environmental groups have regularly come together to defend the thickets. At Horbachykha, the Biorhythm community of sound artists and musicians worked with ‘Save Horbachykha’ to produce a soundscape used for defending the area from development.

Between 2001 and 2014, there were more than 300 activist groups protecting green spaces in Kyiv alone. These were often local interest groups, largely unorganised, and “mainly bothered by the prospect of the eyesore caused by new building developments outside their bedroom windows,” according to Vasyliuk.

Over time, however, the activist community has professionalised, concentrating into fewer but more powerful groups who are savvy with legal matters, and know how to converse with lawmakers and city officials.

**

Part-ski complex, part-urban forested ravine, Protasiv Yar is a green space in downtown Kyiv which has been loyally defended by local residents from development for around 18 years.

The most prominent defender of the site was Roman Ratushnyi. A born-and-bred Kyivan, he became an influential activist at 16 during the Revolution of Dignity, as well as a key player in the ‘March for Kyiv’, which united 40 activist organisations with environmental, educational, city planning, and development concerns to demand a better, more just Kyiv.

Ratushnyi founded the NGO ‘Let’s Save Protasiv Yar’ in 2019 after the city government illegally sold a permit to develop the site he’d loved since childhood.

Having gone to law school, Ratushnyi was emblematic of the new era of Ukrainian activists capable of defending themselves in court, fluent in the language needed to negotiate with those in power, and vigorously against all forms of corruption. In 2021, Protasiv Yar was designated a green zone that could not be built on. His campaign was successful.

On 9 June 2022, Ratushnyi was killed defending Ukraine from Russian invaders close to Izyum in Ukraine’s east. He was 24 years old. His death sent shockwaves through Ukraine’s activist community. Kyivans came out en masse to mourn his death.

Ratushnyi’s legacy is sure to reach far beyond Protasiv Yar. His life’s work is already inspiring others to strive for a fairer, more democratic, and free Ukraine, while through Protasiv Yar, he has ensured that Kyivans are able to wander through and enjoy their city’s historical thickets.

COUNTERCULTURAL THICKETS

The best way to inhabit a city is to dérive. My first time in Berlin involved spontaneously climbing through a hole in a fence out of frustration caused by my failure to take the right U-Bahn twice in a row, which led to me abandoning my plans for the day.

Through the fence, I entered a small wood, wandered past a set of comfy-looking-but-damp couches arranged in a circle, before panicking – honestly – that I’d broken into an airport, which I later found out was Tempelhof Field. This is also how I found Хащі – Hashchi – in Kyiv.

Hashchi is the direct Ukrainian translation of thickets, but has also come to designate one particular thicket. Tucked away in a forested area among a complex of garages, Hashchi is a self-organised community space in the centre of Kyiv that emerged around 2014.

Set amidst a 19th Century street that was abandoned and taken over by nature, the human community there relies on the forest for privacy.

More than this, though, Hashchi is located among steep hills where there is a permanent risk of landslides, making it relatively unattractive to developers. To get there, you need to do “a little bit of parkour,” Oleksiy Radynski, a filmmaker and writer based in Kyiv, tells me.

Radynski, who has spent the last eight years as part of the Hashchi community, describes the space as “a place where many subcultures meet.”

Radynski’s 2016 documentary Landslide depicts some of these subcultures; hanging out with Koptev – whose ‘trash fashion shows’ have been a regular hit at Hashchi – and Vova Vorotniov, a contemporary artist based in Kyiv, who is a key member of Kyiv’s countercultural scene.

Vorotniov is a core member of ETC (which stands for various things, including ‘erase the city’ and ‘enjoy the city’). Radynski describes them as “a post-crew or meta-crew of graffiti artists.”

The group arranges graffiti workshops and occasionally opens a small equipment shop at Hashchi, or at least did prior to the full-scale invasion.

Both culture and nature emerge spontaneously at Hashchi, which usually has no planned programme of events. Hashchi is a safe space, Dmytro tells me, “sheltering people from mainstream urban practices.”

Radynski has never seen a violent incident there in his eight years visiting. But there are occasional clashes with the garage cooperative who do not see eye-to-eye with the Hashchi community, as well as police raids, which are depicted in Landslide. For this reason, Radynski describes Hashchi as “not a public space, but a hideout.”

During the war, however, the use of this space, as with the other thickets, has changed. Radynski hardly goes to Hashchi anymore, reporting as a photographer and writer from the Kyiv region, and curfews prevent people from gathering at night.

FUTURE THICKETS

For Dmytro, the thickets are “uncontrolled zones which nobody owns; between the cracks of neoliberal space, constructed from both Ukraine’s independence epoch, and its Soviet heritage.”

Their complicated legal status – often effectively none – means they are constantly in limbo, and the city pretends they don’t exist.

But it is clear that human and nonhuman communities depend on each other in the thickets. Like other cities around the world, as Kyiv begins to feel the effects of global warming, the thickets play a role in regulating temperature, filtering dust from the air, retaining atmospheric moisture, and absorbing carbon dioxide.

These are key factors that will boost Kyiv’s resilience in a warming and weirding world, especially since it continues to be the world’s most polluted capital. Hmyrianska describes the thickets as the "lungs of the city," while Vyrlytsia Lake is known as the ‘air conditioner of Kyiv’.

Since 24 February 2022, however, the future of the thickets is now more uncertain than ever. Today, as people are forced to flee Russian invaders in the frontline areas of Ukraine, increased construction to home the displaced is likely in Ukrainian cities.

Since 2014, many members of Ukraine’s activist community, like Ratushnyi, have died fighting Russian invaders in the east, or been victims of targeted Russian aggression.

Several activist projects and workshops have been put on hold as these communities are forced to reorient their efforts towards supporting Ukraine’s frontline forces and people injured or displaced by war.

Once spaces of refuge and relaxation, many thickets are now booby-trapped throughout the Kyiv region, having been heavily mined by retreating Russian invaders.

Cases of wildlife dying or becoming injured have been widely reported. While the Russians may have left the forests of Kyiv, nature has become uncanny in their wake, transforming how people relate to these spaces.

But the war is having unexpected effects, too. Vasyliuk tells me that scientists, unable to travel to their field sites both internationally and within Ukraine, have taken to studying their local ecologies. Vasyliuk is encouraging his colleagues in Kyiv to publish their new research, hoping it will inform the protection of the Kyiv thickets in the future.

While rebuilding Ukrainian cities damaged by war, one challenge will be to view green and grey not in opposition, but as complementary and inseparable. From the Kyiv thickets, we have much to learn.

**

Reflecting on how the war has changed his relationship to the thickets, Dmytro drifted deep into a reflection on his family home in Luhansk, which has been under Russian occupation since 2014.

“I wonder what it looks like now, how it’s been slowly transformed by nature over the years, and by other dwellers who came to our empty building. I saw some photos in 2017 from my neighbours who care for the house.

"They showed how our yard has been seized by wild grapes and trees. It’s a process of… not destruction, but reclamation. It’s important to give nature a chance to create something with this empty space.

"I’d like to explore all this: the insects and animals, and the new species which have arrived – the new dwellers. I’m trying to imagine the moment after de-occupation, when I’ll go to the places of my childhood and see these new thickets, hopefully in the green season, spring, or summer. When it’s possible, after our victory, we’ll see the thickets at our place together.”

This Author

Jonathon Turnbull is a cultural and environmental geographer at the University of Cambridge whose research explores nature recovery in the Chornobyl Exclusion Zone. He was a visiting researcher at the National University of Kyiv-Mohyla Academy from 2018-2021, and Ukraine Lab writing resident in 2022.

This article is published in partnership with Ukraine Lab.